posted by kathy

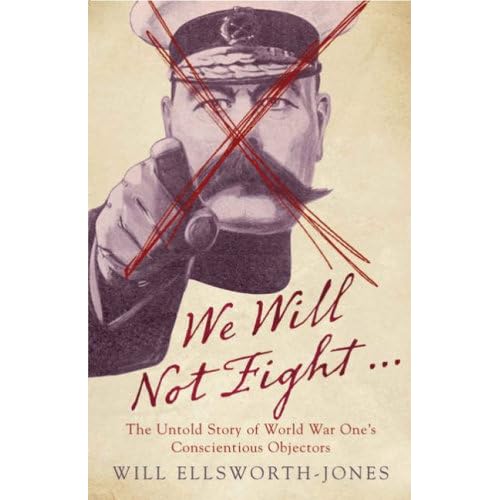

A review in today's Guardian reminded me of the history of pacifist conscientious objection - and how difficult it was. One of the books discussed, We Will Not Fight by Will Ellsworth-Jones, looks at the case of Bert Brocklesby, whose two brothers were at the front. War was against Bert's Christian beliefs (he was a Methodist) but he wasn't granted conscietntious objector status. Instead he was shipped out to France and sentenced to death.

The review, by Francis Beckett, is full of telling quotations and anecdotes about the horrors of the First World War. It wasn't just a time of jingoistic patriotism but also period in which general conscription was first introduced. Most British Christians were war-mongers and the review quotes Archdeacon Basil Wilberforce, chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons, preaching that:

"To kill Germans is a divine service in the fullest acceptance of the word."

It's hard to stand out against trends in the way that Bert Brocklesby and others did. In the twentieth century, Quaker pacifists probably had an easier time than most because they had the support of their Meetings. There was a whole organisation supporting them. They might be sent to prison but I've heard accounts of Quaker Meetings in prison in wartime. Conscientious objectors acting alone and without the support of their churches - like the Austrian Catholic anti-Nazi Franz Jagerstatter - had a much harder time. Bert Brocklesby, who eventually survived, was neglected and condemned by army chaplains:

"Under sentence of death in Boulogne, in a filthy cell, Brocklesby was visited by a chaplain, who held his nose against the smell. "What is your religion?" asked the chaplain. "I'm a Methodist." "Oh, I'm sorry, I can't help you - I'm Church of England." Worse was the chaplain who visited Brocklesby after his reprieve and called him "a disgrace to humanity"."

Today it's pretty well accepted that Quakers are conscientious objectors. But Quakers are also involved, more controversially, in direct action: in the campaign against the U.S. spy base at Menwith Hill, for instance; in protesting against arms fairs and the arms trade; opposing extraordinary rendition, torture and the theft of Diego Garcia from the Chagos Islanders. Meeting for Sufferings (the central administrative committee of the Society of Friends) may be concerned with such bureaucratic tasks and the central framework of the society, but it also considers questions which may be unpopular today - such as the need asylum seekers have for friendship, care and support. And from time to time, Meeting for Sufferings still records the arrest and imprisonment of Friends.

Today it's pretty well accepted that Quakers are conscientious objectors. But Quakers are also involved, more controversially, in direct action: in the campaign against the U.S. spy base at Menwith Hill, for instance; in protesting against arms fairs and the arms trade; opposing extraordinary rendition, torture and the theft of Diego Garcia from the Chagos Islanders. Meeting for Sufferings (the central administrative committee of the Society of Friends) may be concerned with such bureaucratic tasks and the central framework of the society, but it also considers questions which may be unpopular today - such as the need asylum seekers have for friendship, care and support. And from time to time, Meeting for Sufferings still records the arrest and imprisonment of Friends.It's good to remember how people have suffered for their beliefs in the past and to acknowledge how much we have built on the work of people who stood against attutudes, policies and laws which most people now agree were wrong. But that's not enough. George Fox's question "What canst thou say?" still has force. Perhaps we should also ask ourselves, "What canst thou DO?"

Note: The Housmans website has a good list of books on Pacifism and Non-Violence.

No comments:

Post a Comment